Platform business models like Airbnb, Uber, and eBay are upending our conceptions of business, challenging the traditional linear business model as the only the only way of creating value. Today, how a business, public service or charity connects matters just as much as what it produces or provides.

It’s imperative to remember that a platform is a business model, not just a piece of technology. The mistake is conflating a platform with a mobile app or a website. But a platform isn’t just a piece of software, it’s a holistic business model that creates value by bringing consumers and producers together. As such, the platform model can be applied and adapted by any organisation aiming to create value, both internally (between teams and departments) and externally (in the communities they serve and throughout supply chains).

Platforms are not new, medieval marketplaces provided a ‘platform’ for exchange. Then as now, successful platforms facilitate exchanges that reduce the costs of doing business (both time and resources) and enable access to new ideas. The advent of connected technology has simply enabled platform businesses to vastly increase in scale. So platform design isn’t just about creating the underlying technology, it’s about understanding and creating the whole business and how it will create value.

Most organisations, private, public and third sector, are linear businesses, because their operations are well-described by the typical linear supply chain, inputs and outputs. In general, linear organisations create value in the form of goods or services and then sell them or provide them to someone downstream in their supply chain. This applies whether you are extracting and processing hydrocarbons, selling groceries, making cars, or providing education and social services.

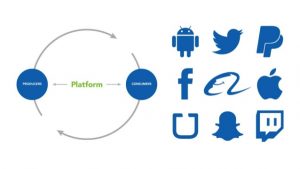

A platform business model, on the other hand, creates value by facilitating exchanges between consumers and producers. Airbnb, Uber, and eBay don’t create and control inventory via a supply chain the way linear businesses do. While a linear business creates value by manufacturing products or services, platforms create value by building connections and facilitating transactions. To paraphrase an old adage: platforms don’t own the means of production, they create the means of connection.

Platforms come in a range of guises. They can be a marketplace for services (Task Rabbit); products (eBay); monetary payment (PayPal); investment (Kickstarter); social interaction (Facebook); communication (Skype); gaming interaction (Minecraft); sharing content, such as a photos or video (YouTube); or software development (GitHub). But they all rely on are four main activities, an examination of which provide clues as to how other organisations might benefit.

In order to flourish a platform business model must first, attract users to join; second, match them together; third, provide technology to facilitate the transaction; and fourth, establish rules that will govern the network in order to build trust and maintain quality.

For platform businesses connecting supply and demand is a chicken and egg conundrum. In order to gain network effects they must attract sufficient numbers of customers and producers. If there aren’t enough producers customers won’t visit the site, and if there aren’t enough customers, producers will stay away. Fortunately, this is not a problem for established businesses, public services or charities, which already have an internal and external audience.

The key then is to connect them. Every transaction needs a producer and consumer: those who have resources, skills, knowledge or experience and those who need them. Understanding your audience enables you to figure out how to maximize the connective value that you can provide. In the first case you need to identify who is in your network and what they have to offer, then you can begin to make the connections (see our January 2018 blog – How to Achieve More With Less). One of our Third Sector clients conducts a “What Matters” conversation with all its new customers to determine exactly what they want and explain what is available.

In order to maintain a degree of control, platform businesses determine their own rules and standards, in order to create the greatest value for multiple users and incentivise the right kind of growth. For example, Twitter’s 140-character limit for Tweets. For a public service or charity, access to the network might depend on adherence to certain health and safety regulations, and procedures for risk assessment. For a business supply chain it might be a quality standard.

With the major functions of the business model determined but not owned, the platform must then focus on creating value by building technology that will facilitate transactions between producers and consumers. In our terms, technology should be understood in its broadest sense, as anything that removes the barriers to transaction. Airbnb. For example, provides software that makes it easy to manage bookings, communication and payments. It also helps hosts to calculate their tax obligations from Airbnb income and provides them with insurance. For other organisations it could be the provision of an information hub; collaboration with other service providers to pool resources and gain economies of scale; offering services to other providers e.g. risk assessment; pre-empting problems by working more closely with your supply chain; or working internally to break down silos.

Most organisations, if they think about it, combine elements of the linear and platform models: they are owners of products and services, and important organisers of connection, but their focus is on the former rather than the latter. And it isn’t just about money, it’s about untapped capacity and value of all kinds, internally as much as externally. In both cases it is about creating an environment to get the most out of people, whether that be sharing ideas and best practice, or collaborating to gain economies of scale and avoid duplication of effort.